I like street:name=*! ![]()

Do you have an example of this situation? If it generalizes beyond a few localities, then a link or photo would make for a good counterexample in a best practices section of one of the relevant pages on the wiki, along with the requisite caveats about local laws etc.

The downside of this contestant, compared against is_sidepath:of:name=* is that the Berlin concept allows more fine grained information, e.g. is_sidepath:of=* to tell the kind of roadway, which can help both routers in choosing a pleasant itinerary as well as QA tools in e.g. finding sidewalks missing out a street:name where the street actually might have no name, e.g. lots of the service type.

But yeah, as a firm believer that streets are shared use public space I’d suggest to use street:name on the separately mapped carriageways as well ![]()

My general impression of the is_sidepath=* proposal and followup is_sidepath:of=* proposal is that, like the highway=path proposal, they try to do too much at once with a single unified tagging scheme. The awkward syntax is a predictable symptom of this overloading.

There will necessarily be a limit to how much situational context we can express through tags. abutters=*, tree_lined=*, and lit=* can all influence the pleasantness of driving on a road, but over time we’ve tended towards mapping the abutting buildings, trees, and street lamps in their own right, because these things have value to map users apart from their contribution to the street’s character. I don’t suppose that we’d now start tagging each house with whether it fronts a (presumably quiet) residential road or a (presumably noisy) primary road, in order to facilitate real estate use cases. Or whether each driveway leads to a busy street with a high speed limit – after all, high-speed cross traffic makes it terribly challenging and time-consuming to reverse out of the driveway.

Some of these determinations and assumptions are squarely in the domain of postprocessing and map matching. The skepticism of map matching in this and other recent threads ignores the fact that the sidepath proposals presuppose that data consumers rely on map matching in the first place.

All we’re asked to consider for the first proposal is a flag indicating whether the way is a “sidepath” or not. That will do nothing to enrich pedestrian guidance instructions unless the application uses map matching to obtain the parallel street’s attributes. But map matching is already capable of finding the parallel street regardless of any “sidepath” hint. After all, the main use case of map matching is to clean up a noisy GPS trace that has zero attributes.

Rather, I think the only benefit of is_sidepath=yes is that it would tell the router it’s appropriate to backfill the name of a parallel street instead of telling the user to follow a nameless path. If this is the case, then footway=sidewalk, cycleway=sidepath, and path=sidepath already provide the same information through iterative refinement, without the awkwardness of naming a database key as if it’s a Python variable.

For the second proposal, the authors have come up with a shortlist of attributes that contribute to the identity of the parallel way: the classification, name, and number. This is intended to enrich pedestrian guidance instructions, but if map matching can already identify the parallel street, with or without is_sidepath=yes, then what’s the point of adding both the parallel street’s classification and name directly to the sidepath?

Ostensibly these additional hints let the map matcher break a tie where two candidates are equally likely with the same name but different classifications. But a tie of this sort will be very uncommon in practice, because a map matching algorithm does not behave like a naïve nearest neighbor search in PostGIS or Overpass: it considers the past and future progression along the route, avoiding discontinuities to the extent possible. And so what if the two candidate matches share the same name – would the choice of a highway=residential over an identically named highway=unclassified have any bearing on the guidance instruction?

I favor street:name=* as a logical progression of bridge:name=* that places roughly the same burden on data consumers as addr:street=*. This minimalist hint is not without its flaws, but it strikes a good balance between maintainability and reliability. Yet I also don’t consider it strictly necessary to put down everything we’re doing and achieve full coverage of street:name=*. Improving coverage of sidewalk:*=separate is more urgent for keeping pedestrians off the street when there’s a better alternative. And for every edge case requiring a mapper’s manual annotation of street:name=*, there will be at least as many edge cases where the correct name to announce depends on where you’re going.

We moved those sub tags to Proposal:Key:is sidepath:of - OpenStreetMap Wiki to keep the main proposal Proposal:Key:is sidepath - OpenStreetMap Wiki focussed. Having both tags in one proposal made discussing them more complex which did not help either of those ideas. Personally, I consider the proposal of is_sidepath pretty stable but the idea of is_sidepath:of:name still very much up for debate with street:name a clear alternative.

Feel free to update that proposal to reflect the state of discussion.

(Disclaimer: I did not read the thread; just wanted to give some context on the topic I was pinged on.)

Ref the discussion “is the sidewalk part of the street or not”, according to the Norwegian transport infrastructure writer Ulrik Eriksen it is.

Sidewalks were originally created to make a dryer area for the pedestrians to avoid all the mud in the main part of the road. It later also became a security-measure to avoid being run down by cars. In 1920 at least 15 pedestrians were killed in Oslo by motorists, even though there was only 2000 cars in the city!

So yes, IMO sidewalks do have a name just like the carriageway for cars/bikes. The concept “street” encompasses the whole thing

I think the road or street encompasses all parts of it, including cycleways/lanes and sidewalks. The center line represents that and holds common information about the whole road, including name. Where two physically separated carriageways are mapped as separate ways, it’s most practical to repeat the name on both ways. ( I suppress my Oracle instincts telling me this is not right in a database ).

street:name=name looks very practical to me, for the purpose of indicating the name to be used in navigating instructions, while avoiding over-labeling on maps.

Conceptually I think it’s not ideal - it doesn’t name an object, it just repeats information that’s already there, to ease up data use processes. But practicality wins, in this case, for me. For mappers, either way it’s one tag.

I have two mapper’s thoughts:

- It’s not always a street; lots of sidewalks are along unpaved and/or non-urban roads or cycleways.

- For separately mapped cycleways along roads it’s the same issue. In Nederland, it is extremely common for roads to have cycling paths along all kinds of roads, urban and non-urban. I think the explicit limitation to sidewalks should be lifted from the definition of street:name.

Let me remark some aspects, as one of the authors of the is_sidepath proposal.

The proposals is_sidepath and is_sidepath:of are actually two completely different things: “is_sidepath” describes the property of a path, whether it is roadside or not. IMHO this should not just be understood as a “matching problem”: For many applications, especially when analyzing bicycle infrastructures, it is important to distinguish between “roadside” and “independent” paths. “is_sidepath” is therefore first of all an attribute for the type of cycling infrastructure/the design of guidance of a path, regardless of which path it actually belongs to. Only when this information is required does it become a map matching problem. This is similar to sidewalks: if you are working with OSM data on sidewalks, you don’t want to perform a map matching process to identify which footways could be sidewalks. This matching process fails in many edge cases anyway and a hint like footway=sidewalk or is_sidepath=yes can greatly improve the matching.

“is_sidepath:of” moreover is a kind of tagging relation to transfer “important” properties of “its” street to the way running alongside the street. We actually only intended this as an experiment in Berlin to see whether it would bring benefits - we are no longer actively following this approach and have therefore also removed it from the proposal. Personally, I also prefer the street:name approach meanwhile.

I wonder if the same rule can apply to car roads too? Just an example from Poland

As You can see the name “Aleje Jerozolimskie” appears on SIX different lines. Maybe it would make more sense to put the name on two main carriageways only and use street:name for the rest?

Thanks for sharing this historical perspective. OSM’s sidewalk tagging proposals and imports have largely focused on the suburban-style sidewalks that predominate in North American cities and suburbs these days, but their urban antecedents did have a somewhat different relationship to the street. In some ways, the contrast between the sidewalk and street was even greater back then:

Because sidewalks were useful and cheaper than roads to pave, they were surfaced with durable materials at a faster rate than the roadbed. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, sidewalks were primarily surfaced with gravel, but by the 1890s, cement sidewalks became common, although roadbed surfacing was still primarily gravel. Sidewalks became cleaner and better paved than carriageways. Pedestrians used sidewalks to avoid traffic, which undoubtedly influenced their decisions about where to walk, and they also preferred sidewalks because they were less muddy than roadways in wet weather and had more even surfaces. Even though photographs indicate that pedestrians “jaywalked” or could step into the street at any point, they appeared to walk primarily along the sidewalks.

(Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia; Ehrenfeucht, Renia (2009). Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation Over Public Space. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-2621-2307-5.)

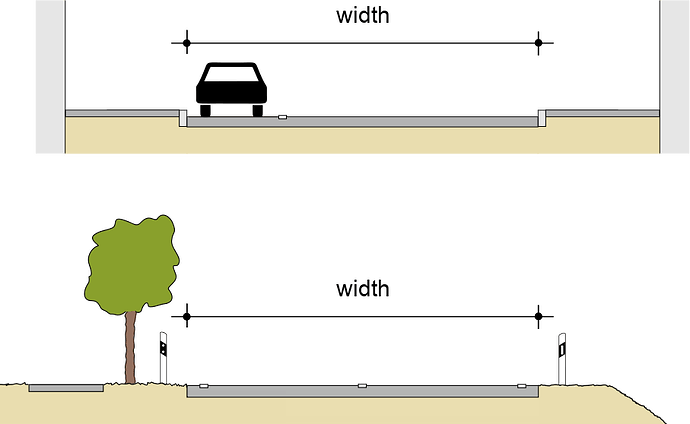

Regardless of broader social norms, which vary by culture, OSM uses highway=primary et al. as an abstraction of the carriageway, not the broader right of way or streetscape, which we often call “the street” informally. This is nowhere more apparent than in our definition of the width=* of a street:

I fully agree. Heuristics like map matching for names only make sense for some kinds of walkways and not others, so we want the router to apply them conservatively based on keys such as footway=sidewalk instead of inferring the classification based on geometry. Otherwise, the router may not know that the walkway is actually independent of the nearby street, for example because there’s a retaining wall between it and the street.

OSM routinely conflates the concepts of streets, roads, and highways. We see that with other keys such as addr:street=*, destination:street=*, and route=road. On the bright side, this keeps us from wasting energy on megathreads about whether a stroad is a street or a road, or whether an expressway is a road or a highway. (If only mappers could rule the world, we’d make it much easier to classify!)

In principle, street:name=* could’ve been called highway:name=* to more obviously lean on OSM’s definition of highway=* than any plain English word. But that key is already being used for the name of the highway feature itself in some regions. For example, this road in Japan and this street in Hong Kong are named Tokyo Minato Rinkai Road and Connaught Road Central, respectively, but these names got relegated to highway:name=* in favor of Rinkai Tunnel and Pedder Street Underpass. I would’ve expected the street name to go in name=* and the other names to go in bridge:name=* and underpass:name=*.

To make matters worse, sidewalks also commonly run along the edges of parking lots, which don’t even fall under the highway=* key. In fairness, is_sidepath:of=* illustrates the difficulty of finding an intuitive word for the traversible thing, whatever it is, that a sidewalk or sidepath has been separated from but remains subordinate to. Can we get away with this imprecision by clearly documenting for data consumers that they shouldn’t assume this thing is a particular subset of highway=* values?

An earlier draft proposal for street:name=* was limited to sidewalks and crosswalks, but I didn’t notice it when I wrote up the street:name=* documentation in haste the other day. Instead, without looking closely at existing usage, I made sure to always state “sidewalk or sidepath”. It sounds like you’d be in favor of keeping that carveout for sidepaths, which would include bike paths, right?

It depends on the region, but in general, link ways don’t need to be named unless they have names distinct from what they link. Some jurisdictions signpost systematic names or identifiers for emergency use, but we put them in other keys, such as carriageway_ref=* for the slip road letters in the UK and official_name=* and destination=* for the “Ramp A to B” names in Ohio.

As for the parallel residential road, this is a frontage road which comes with somewhat different considerations. In my experience, frontage roads carry independent names much more frequently than sidewalks. If the name matches the main carriageway, it’s usually the remnant of a historical upgrade of a surface street to a freeway. The analogy here would be if something that had always been a named pedestrian street got converted to a conventional street, leaving walkways on either side with the original name.

Works4me!

Works4me2!

A recent example was sidewalks added to Bathurst Road in NW London by one of Meta’s mapping team, which would have added half a kilometre to crossing the street. I explained the problem in a changeset comment and they were happy for them to be deleted. See changeset #159178901.

I’ll try to find some other examples after the long weekend.

Yes, they exist in Pompeii and there are even stepping stones to allow pedestrians to keep dry when crossing the road.

I assume cart wheels were a standard pitch.

They were indeed, for reasons described in this article (which then goes on to somewhat debunk a number of other myths sometimes related to that).

This, ahem, documentary gives an idea of that sort of common street layout (location here).

In case you use Cyrillic it’s not so confusing in pronunciation as in Latin ![]()

Turn left into Sczebrzeszyn street → Поверніть ліворуч на вулицю Счебжешин

Now that you transliterated it, I realized something was odd: @Mateusz_Konieczny misspelled it himself ![]() – it should be Szczebrzeszyn, hence Шчебжешин (or Щебжешин, depending on transliteration scheme).

– it should be Szczebrzeszyn, hence Шчебжешин (or Щебжешин, depending on transliteration scheme).

Made me curious!

- how that breaks down, and

- how much stems from misuse of “this is a sidewalk” when it’s just a regular pedestrian path

…since I see barely any near me and it also seems very confusing to try to squeeze in those two metre-precise extra ways between the buildings, roads, possibly parking spots and tramways, etc. Much easier to go on StreetComplete and tag what the layout and features of this way are, so I was curious if this is a lot of misuse and one super active region or so

TL;DR:

- Basically north america (CA,US,MX,CU,…) has 55% of the world’s distance in separately mapped sidewalks, with the other regions being basically a map of how well OSM is mapped (e.g. Europe is next with 22%). (There is also 4% unaccounted for, that must be on islands that I didn’t include in any continent’s bbox.)

- No, some countries genuinely have a lot of separately mapped sidewalks

Separately mapped ways seem to shoot up when countries are sparsely populated. From spot checking, I could not find a single questionable use in Iceland, one out of a dozen spot checks in Norway, and within maybe five checks in the USA I found one park that had a section marked as “sidewalk” (without being near any non-footway). The USA and unmentioned regions might warrant further inspection but it’s not super widespread at least: the vast majority that I saw was correctly mapped and followed some road – even if that is a motorway/expressway (saw that one in Oslo iirc).

Data dump regarding question#1

-

Europe

-

Africa

-

North America

-

South America

-

Asia+Oceania

-

Oceania

-

UK

-

Nordic European

PS. I’ve moved your popularity mention on the wiki down to the section titled popularity, with a sentence in the original spot linking to that section. Hope that’s okay! Feel free to rework the popularity section, including what I wrote. I think it could use some cleaning up but I’m not sure what to best remove, e.g. should the discussion about raw usage counts be removed now that we have distances? Things like that

If anything, the statistics I posted are a significant undercount. I very frequently encounter bona fide sidewalks missing the footway=sidewalk tag, and the statistics also don’t account for crosswalks, which really add up in larger cities.

Intuitively, I’d expect misapplication of footway=sidewalk to be quite rare. This thread is the first time I’ve ever seen the confusion come up, despite following near-daily discussions of sidewalks and other pedestrian infrastructure on OSMUS Slack for years. In the real world, using “sidewalk” to mean all walkways is widely understood to be an informal colloquialism. I suspect the real reason for the earlier confusion here is that “Foot Path” is a misleading name for highway=footway in American English. (“Motorway” and “Motorway Junction” are similarly problematic.) We only get away with it to the extent that the user also notices the “Cycle Path” and “Bridle Path” presets right beside it.

Sure, no problem, I hadn’t noticed it. (For reference, we’re talking about this section.)

The raw element counts aren’t meaningful and are actually quite misleading: we normally split roads for a variety of reasons, but conversely many mappers will draw a single sidewalk way all the way around the block. A more meaningful statistic would be the number of mappers who use either method, but I don’t know a straightforward way to gather that information. The section explores these issues at length to dispel a popular misconception that arose previously and in this thread. I’d keep this discussion for now, but maybe we should have a dedicated page explaining why raw element counts can be misleading in general, using sidewalks as an example.

Your hypothesis about population density is interesting and a plausible correlation at a national level, but I don’t think it holds at a subnational level. The biggest, densest cities in the U.S. tend to have better coverage of sidewalk ways than mid-size cities, due to a combination of more local mappers, more interest by paid mapping teams, and access to higher-resolution imagery and much more street-level imagery.

I think there are three main reasons for the cross-Atlantic divide:

-

The U.S. almost always builds sidewalks with some kind of separation, either a curb or a verge. Level, unseparated walkways are mostly by accident rather than by design (i.e., repaving the street enough times to raise the street surface to sidewalk level or beyond). Meanwhile, German-style sidepaths are rare enough here to be unrecognizable as a standard pattern, because cyclists have generally been expected to share the road with motorized traffic.

-

In the U.S., jaywalking is socially unacceptable, largely unlawful, and generally unsafe. This is also true to some extent in some parts of Europe, but the social norm is much stronger here. It strongly affects user expectations, especially by those with special mobility needs.

-

In OSM, Europe had a head start of several years. By the time the U.S. community gained critical mass, we had access to better imagery, and micromapping had already become entrenched in global OSM culture, making sidewalk ways more plausible. Routers were starting to come online, allowing us to experience firsthand the benefits of a clear routing network. Some cities, including Cincinnati where I map, had an existing body of

sidewalk=*tags, but only due to a now-discredited tagging philosophy that also entailed gluing all landuse areas to roadways.

Sure, both will exist. I was just blown away by the sheer amount of separately mapped paths when considering that adding the tags to the original way is like two taps streetcomplete or adding a tag in your favorite editor. compared to carefully tracing out, aligning, connecting, and tagging a new way. Hence me looking in that direction

I’d imagine most use both, since they each have merit in different circumstances — at least that’s what I do