If alt_name=* seems like a “graveyard”, it may be because few if any rendered maps label features with alternative names. But alt_name=* is very well supported among geocoders, likely better supported than these -t- extension subkeys. On the other hand, if you’re focused on “representing truth” rather than practical usage by data consumers, then I don’t see how it would be a graveyard, since the tag is just as accessible as any other name tag in the raw data.

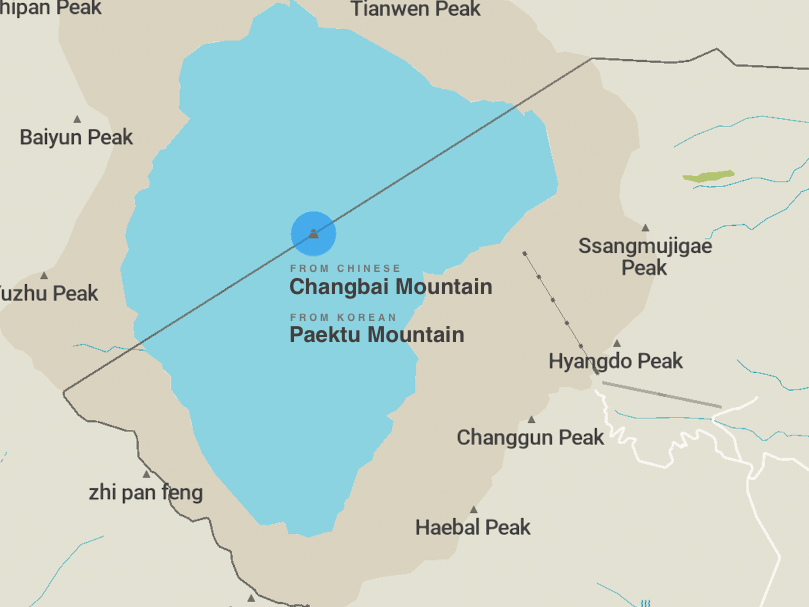

Thanks for bringing this to my attention. It’s a good example of the complex state of Vietnamese exonyms. Here are the most common names for this mountain (with demotic Han in parentheses), ordered from most to least traditional:

- núi Trường Bạch (𡶀長白): native Vietnamese núi (𡶀, “mountain”) + Trường Bạch (長白), Sino-Vietnamese transcription of Chinese 長白山 (= Sino-Vietnamese Trường Bạch sơn, “as-far-as-the-eye-can-see white mountain”)

- núi Bạch Đầu (𡶀白頭): native Vietnamese núi (𡶀, “mountain”) + Bạch Đầu (白頭), Sino-Vietnamese transcription of Sino-Korean 백두산/白頭山 (= Sino-Vietnamese Bạch Đầu sơn, “white head mountain”). Đầu is also considered a native Vietnamese word for “head”.

- núi Paektu: native Vietnamese núi (𡶀, “mountain”) + Paektu, McCune–Reischauer transcription of Sino-Korean 백두산/白頭山 (= McCune–Reischauer Paektusan, “white head mountain”)

Sino-Vietnamese is properly defined as the variant of literary Chinese associated with Vietnam (lzh-Latn-VN or lzh-Hani-VN). Individual Sino-Vietnamese words are read (pronounced) like Vietnamese words, but the grammar is archaic Chinese, closer to modern Chinese (zh) than Vietnamese. For example, the character for “mountain” comes first in the Vietnamese names but last in the Chinese, Sino-Korean, and Sino-Vietnamese names.

For most parts of the world, people in Vietnam regard Sino-Vietnamese exonyms as quaint, even obsolete, if they understand them at all, whereas overseas speakers regard non-Sino-Vietnamese exonyms as lazy code-switching, if they understand them at all. However, it’s even more complicated in the Sinosphere.

Historically, Vietnamese speakers used Sino-Vietnamese exonyms for everything Korean, but in the last few decades, people in Vietnam have switched to Revised Romanization for South Korea as the two countries have normalized relations. This sometimes bleeds over into using Revised Romanization for North Korean names too, just for simplicity, but Sino-Vietnamese is more common, and there’s the occasional McCune–Reischauer as in núi Paektu. Often Vietnamese speakers just use whichever name happens to be handy, regardless of its etymology. On the other hand, some writers embed the unadulterated Sino-Vietnamese name directly into Vietnamese text, for a more literary feel.

How to boil all these nuances down into a seven-character code? You can’t.