Taking a step back from the most recent flareup, I’d like to reflect a bit on the “on-the-ground” verifiability principle. Verifiability is an important rule for any online crowdsourcing project with as low a barrier to entry as we have, and especially important for any map that people trust as part of their daily lives. Both sides of the abandoned rail debate have passionately invoked the verifiability principle, both in this thread and in the parallel German thread. Who is right?

There’s often more than one way to verify a fact about the world. Scientists distinguish between observation and inference. OpenStreetMap is built around the ethos that each of us is an enterprising surveyor, GPS unit in hand and bedecked in full high-vis regalia. Anyone can do it! Of course, the reality is that most of us end up staring at aerial imagery most of the time instead. Anyone can do that too! Either way, this is mostly an exercise in observation. But usually we don’t just record what we see verbatim; we apply local knowledge or common sense in interpreting these observations. This is inference.

Both observation and inference have a place in OSM. Observation matters somewhat more, as it aligns with OSM’s goal of democratizing mapmaking, but it’s insufficient. There’s a reason no one likes to hear, “Don’t map [the thing you wanted to map]; just map the signs!” Robots can just map the signs, but we are not robots. If we were to take a fanatical stance of mapping only pure observations, then OSM’s landuse coverage would consist of nothing but coloured polygons, no different than posterizing satellite imagery, a cheap trick that some proprietary maps like to employ to seem like they have more detailed coverage than they really have.

A venture capitalist once asked me why I waste my time contributing 3D buildings and navigation details to OSM when the future is clearly in LiDAR point clouds and HD mapping. I wasn’t going to win him over with a diatribe about licensing, but I did have this to offer in our defense: against a constant drumbeat of automation, OSM provides unique value by inferring semantics from our observations. (I left that encounter empty-handed anyways. Oh well.)

On the other hand, a crowdsourced project can only admit inferences up to a point. On the Internet, no one knows you’re a dog with a postdoctorate degree in ferroequinology; you could just as well be making it all up, and we need to be able to tell the difference. A darkened strip in a field, visible only from the air – is that the residue of a former trackbed, a crop mark left by an ancient wall, or a geoglyph of unknown meaning? When a self-professed railfan excitedly proclaims it to be a trackbed, one hopes it’s because they have other corroborating evidence or external context to make that inference. I can cite my personal experience or professional expertise, or Occam’s razor, but to the community it can look like a personal bias.

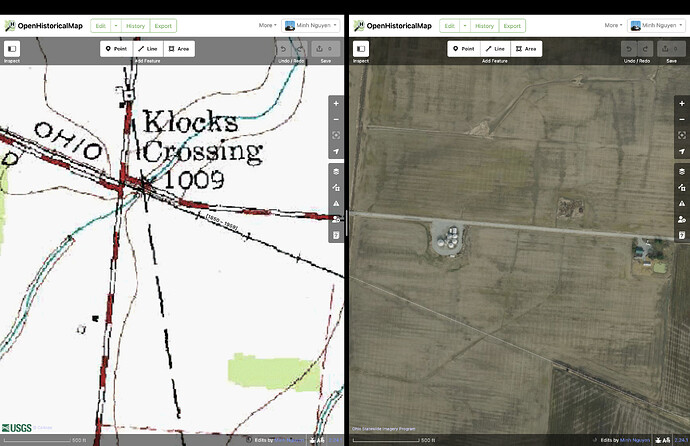

OpenHistoricalMap does things differently than OSM, by necessity. No one has developed a FOSS time machine yet, so observation can only get us so far. With observation alone, we cannot fully tell the story of a people molded by colonialism, of a minority community that was wiped out by freeway construction, of human folly that was smitten by a natural disaster. Without any observable details, any inference becomes rank speculation. This is why OHM prioritizes a third method: research. We want mappers to show their work: if you consulted a newspaper article, cite the article. If you traced an out-of-copyright map, tag the georeferenced map’s URL. If you had to guess a date out of a range of possible dates, there’s a syntax for that. And if you just came in from a field survey, that’s fine too.

Whenever tensions flare around abandoned railway mapping in OSM, I’m saddened to see someone distort what is clearly their personal passion in order to somehow shoehorn it into OSM’s rules and methods. Yes, it’s true that someone with a keen eye can spot a former trackbed in a field. Yes, as someone pointed out in Slack a couple years ago, a diver could potentially verify that these tracks from chapter 35 of Kudish have not yet disintegrated in the lakebed. But then what? Is that all there is to say about the Fonda, Johnstown and Gloversville Railroad? Whose idea was it to build a submerged railroad track, anyways? This rail coverage is devoid of context that would help users learn anything from it.

I would like to think that folks like @TNS-MN are actually conducting research, even as they try to pass it off as observation. Imagine how much happier and more productive they’d be if they could map their research, without having to make excuses. This has been my experience interacting with roadgeeks who similarly care about transportation history. One mapper in my area kept fudging rural highway classifications and mapping abandoned road alignments as the real thing, while making bold claims about improving the mobility of rural Americans left behind by Silicon Valley mapping companies. I wasn’t involved with OHM at the time, but I mentioned it to them and they took it very seriously. They quickly became one of OHM’s top road mappers in the U.S., unshackled from OSM’s arbitrary rules against historical mapping.

Both OSM and OHM need more success stories like this. I’m not much of a railfan, but I’ve never had more fun mapping abandoned railway lines than I have since joining OHM.

To be sure, research is hard. One thing leads to another and you wind up with too many tabs open. I spend hours poring over planning documents and newspaper archives just to be able to add a single building to the map. If a mob of mappers started musing about deleting my work, I’d take umbrage too. It’s not as easy as re-observing and re-mapping.

Despite the challenge of conducting rigorous research, there’s a certain joy in knowing that it’ll help someone connect the dots: why does the building have such a funny shape? What happened to the business that lent its name to the building? And guess what – anyone can do it, because unlike in other historical GIS projects, OHM wants everything to be mapped, even if academicians in an ivory tower would not deem it to be historically significant. I have mapped a favorite ice cream stand from my childhood and it gave me great pleasure. Take a break from the Internet, enjoy some ice cream, and then come back and share it with us on OHM.