I’d even go a step further and encourage rail mappers to redundantly sketch in some extant railways there too, so that one can see the old rails in the context of the present system. In general, OSM will always have more detail than OHM regarding extant features, such as more precise geometries, signaling, voltages, and work rules, but OHM can be the place to go for the basic information in a historical context.

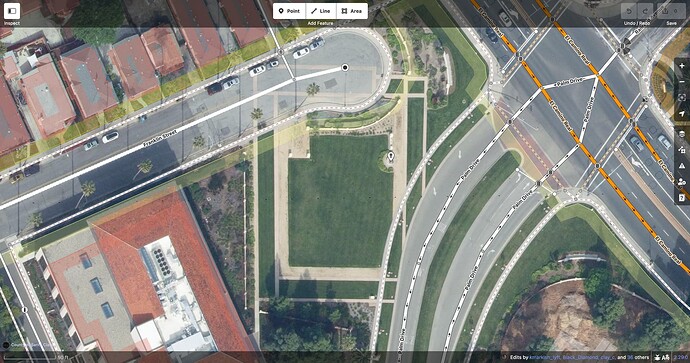

How about this pattern on a university campus that marks out the footprint of an 18th-century Franciscan mission?

This isn’t the actual foundation, just a memorial to it. Should there still be an abandoned:building=yes? Should it extend across Palm Drive? (Presumably the Franciscans didn’t anticipate this road by building a weird notch into the building two centuries beforehand, but both my source=local_knowledge and my source=survey are failing me here.)

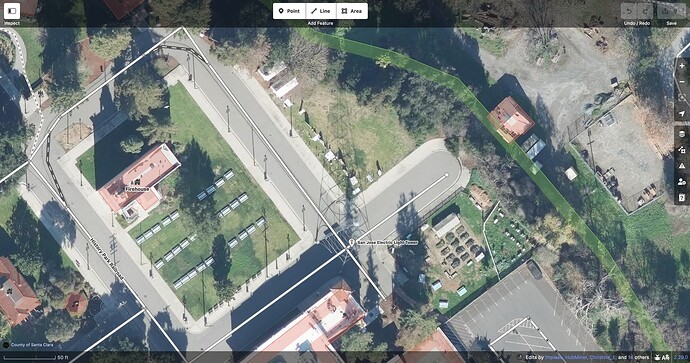

This light tower shining on an outdoor history museum is just a replica of one that blew over in 1915. Obviously, I can map it as a light tower…

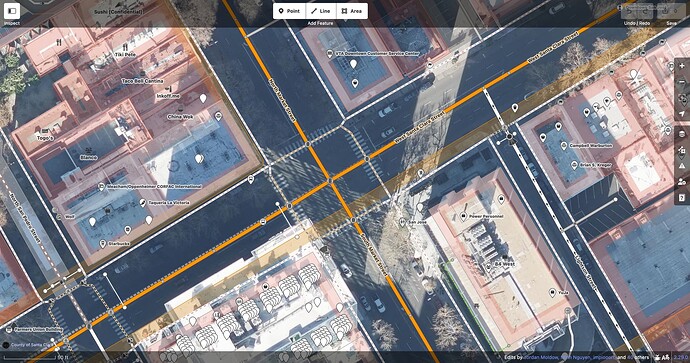

But the plaque at the foot of it also gives me enough information to map the original tower miles away, in the middle of the most important intersection in town, where there is no trace left of the tower, just standard traffic signals. Should I map a demolished:man_made=tower in OSM as well as OHM?

When I last wrote about this disused railway bridge along a rail trail, a park crew had just come and dismantled it. The best-case scenario is that they’re going to move it to a park to serve as a curiosity, like this old covered bridge. In the meantime, it’s likely living out retirement in a warehouse. When the time comes and we map the bridge area at the new location, should we leave a copy at the old location, based on the trail’s slight jog to the west and some possible fragments of an abutment? After all, this is a former bridge, right? Or was it a bridge? Or is it still a bridge, but in a different location?

I don’t think the answer to any of these questions necessarily rests on whether the feature or its backstory is interesting or enlightening. A map aspiring to be like OHM would need uninteresting things too, or else history would look too patchy to make sense of.

The issue I see is that OSM policies, tools, and practices aren’t optimized for mapping historical geography with any degree of seriousness. For starters:

-

Verifiability is primarily based on ground observation. This is a problem when a defunct railway station is only attested in an old topographic map or timetable, or the former name of a street is only attested in newspaper articles (which themselves are still under copyright). How should these sources be cited, to avoid charges of plagiarism?

-

“One feature, one element” prevents us from mapping the sometimes significant evolution of a feature’s geometry over time. This leads to definitional challenges for the two most important attributes in historical geography,

start_date=*andend_date=*. Even if one can get past all the wiki’s admonitions to abstain from these two keys,start_date=*refers to different events in the lifecycle of a work of art than it does a building, and there are probably more exceptions that aren’t documented. -

An automated bulk import of historical geodata would a nonstarter. Not that there would be many opportunities to perform such an import: despite a wealth of historical datasets out there, their authors, some of whom depend on attribution even more than we do, would chafe at the ODbL and its insistence that OSM contributors get credit while they get relegated to a mere changeset tag that downstream end users won’t ever have access to.

These stances prevent software developers from writing tools to facilitate historical mapping and significantly limit the ability for OSM data to faithfully represent the past. However much one sympathizes with abandoned railway mappers, historical features are at best a second-class citizen in OSM. One can certainly learn to appreciate historical geography by going on a scavenger hunt for relics and artifacts, but that isn’t the same as learning or teaching historical geography – just ask Dr. Indiana Jones.

On the bright side, historical geographers can still cross-reference OSM with other sources for a fuller picture. Lifecycle tagging in OSM can serve as hints for further research elsewhere. If a user or mapper comes across a little bit of real-world history reflected in OSM, it might spark an interest that grows into something larger. Just don’t fall for the trap of thinking that everything has to go in one database.

OHM still has many unresolved questions about how to model historical geography. But critically, it takes a research-oriented approach, with the classic OSM twist of welcoming amateur historians to pitch in – as long as they adopt more rigorous sourcing practices. Some abandoned railway mappers have held out hope for a grand OSM–OHM merger so they can keep doing what they do without learning new tricks, but it would require a huge change in philosophy for OSM, a bit of the tail wagging the dog. Why wait for that when there’s so much opportunity to shape a nascent project’s future, and so much fertile ground for mapping? I don’t want to ever hear anyone complain again that they’ve locally run out of things to map!