Good question. I think that yes, this discussion is broader than New England, but it is possible that New England is the only part of the country that is completely out of whack due to its history of development and municipalities being named “Town” rather than “Township” in a way that confuses people trying to assign values to the place hierarchy. As well, many New England states have little or no unincorporated area and no county governments, so “Towns” are large and sometimes sparsely-populated administrative areas here.

In other parts of the country with County-level government Towns/Cities/Boroughs were formed by carving out a densely populated part of the County for self-government, leaving the less populated portions outside of the incorporated territory. This makes those towns much more likely to fit the OSM place=town definition than the “New England Town” as they had a dense enough population to bother incorporating.

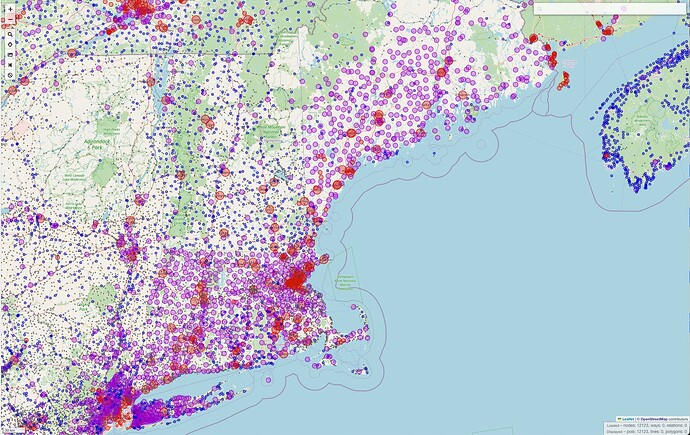

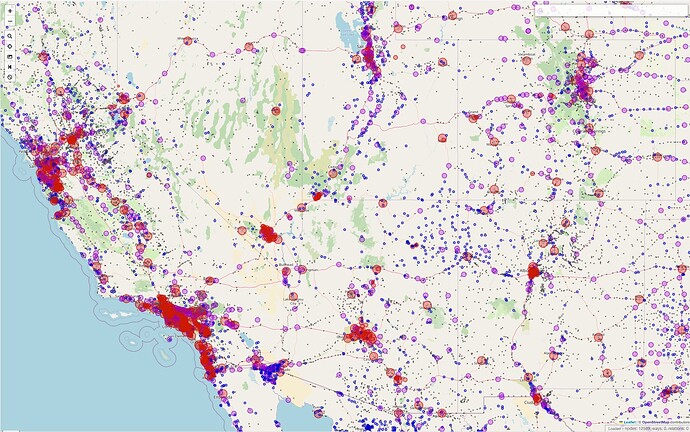

Using this Overpass rendering of place=* nodes it doesn’t seem that the rest of the country is as miscategorized as New England:

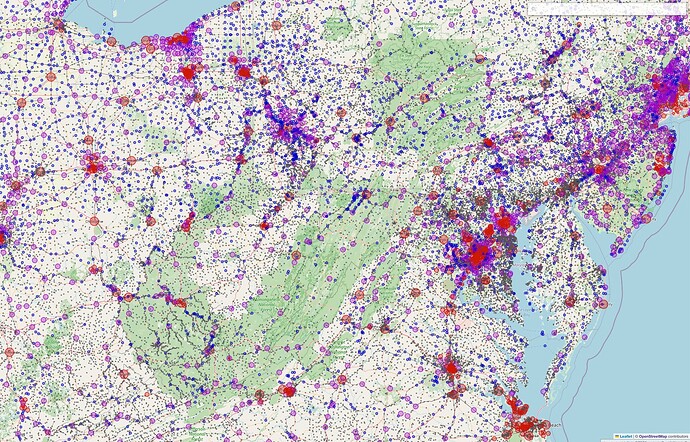

Mid-Atlantic and Southeast seem like they have a reasonable distribution of cities/towns/villages/hamelts:

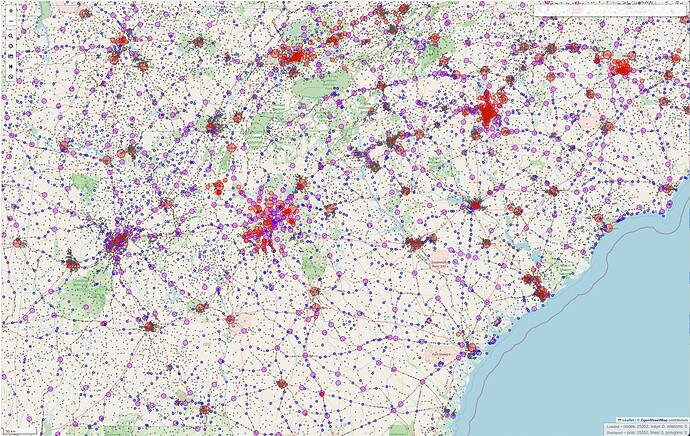

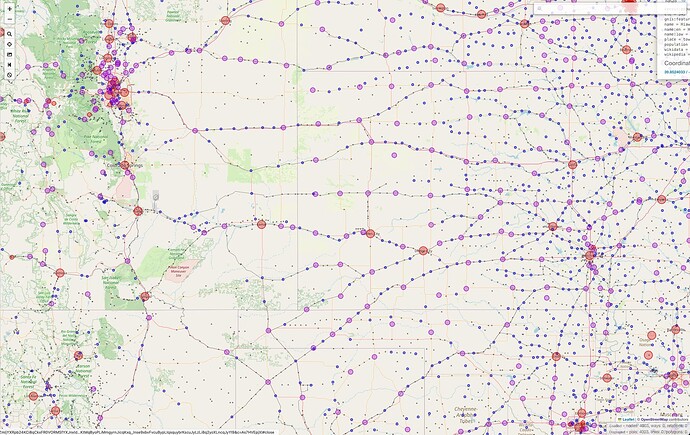

I don’t have enough local context to know if the Midwest and plains are over-classified or not:

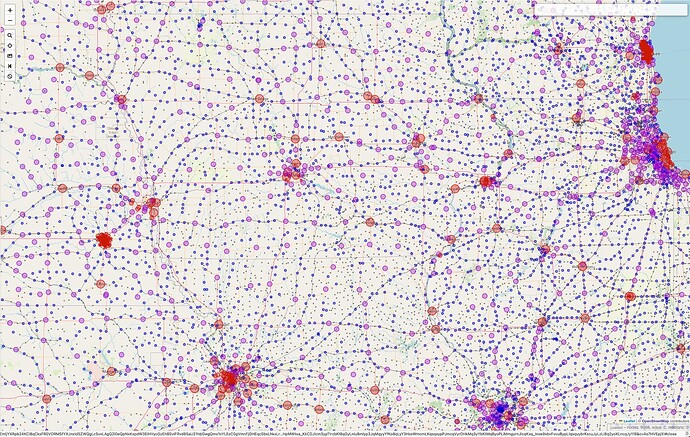

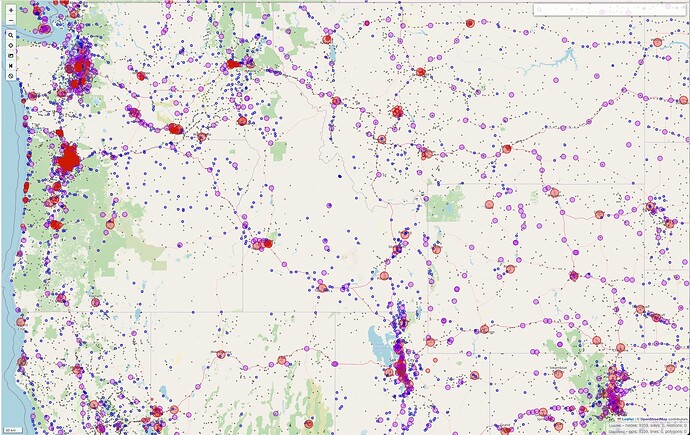

The west looks much more distributed overall, but Wyoming has a bunch of place=town with populations < 100 which may or may not be appropriate given how little else there is out there:

Long story short, New England is a particular problem but we should try to solve the overall classification with an eye toward a national standard.