Is a route really a path?

Sould OSM have a road that has no visible signs of being a road rendered as a clearly distinct type of road? Or something which isn’t a road?

Should a route which has no visible signs of being a path, and on which the desired route may be far away from where it is rendered as a path, be treated as a discrete path?

For a route that goes through over 20 miles of a narrow river canyon, is it feasible to map out every sandbar that comes and goes?

I can think of “routes” where large sections of them are passible, and then there is a point or two where it narrows down.

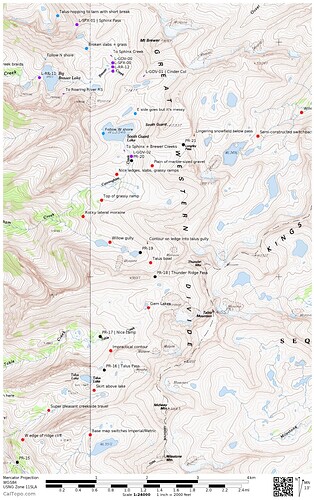

The following pass is roughly under the yellow dot. My partner and I just walked the talus to the right along the lakeshore (our camp was on the outlet side of the lake on a durable surface), then made our way up simple grassy ramps and broken granite slab to where there are two T4-5 ways to gain the ridge.

The top of the pass has two easier climbing ways to gain the ridge near each other. This is one. Note it’s all relatively simple XC below.

Up until that specific point to (relatively) easily gain the ridge, there could easily be hundreds of links that show a possible way that is sometimes useable. Someone could come from the other side of the lake, traverse high from Ramstein Pass just to the left, or drop further on a traverse over from Goddard Pass. If someone just really didn’t like talus (it was all stable down by the shoreline, we didn’t mind it) they could take the long way around the lake.

This particular pass isn’t along the Sierra High Route, or the SoSHR, or any of the Skurka ones or the new traverse one etc so it shouldn’t qualify as a route in the OSM sense. That said it’s not that unusual a use case and an obvious one that comes to mind I have photos for.

See also the coastal route photo up above. Where is the precise location for proper link here? Where I was, where my partner was? She wasn’t anywhere in particular, and that log won’t be in the same spot for all that long. Just the entire area below high tide and low tide + isolated bits of passable terrain above high tide?

This is I think a useful distinction and probably one of the only useful ways to have something of any real length with trail_visibility=no.

What is the precision we are looking for here? I honestly struggle to think of a pathless route of any length where people will consistently follow a precise path.

I’m sure we’re all familiar with coming across an area where 3-4 different informally cairned routes suddenly appear (or in some cases dozens). In theory those could all be mapped, but in reality they’re arbitrary paths created by someone that’d fall under “don’t upload your personal GPX route”. I can think of say where the unmaintained (de facto if not de sure) trail peters out going up the hilgard fork of bear creek. iirc I went along the middle route, then deviated from it as I felt like doing. None of those routes, or possible links, were meaningfully different from another in terms of difficulty or safety.

Do you want to be closer to the stream, up in trees, walking across a slab? It depends on personal preference, weather, if the slab has water coming down it or not, etc etc.

So…

What makes something consistent? Over the course of kilometers of hiking, are people’s routes always within 20m of each other? 3m? 10m? 100m? 250m? At what point does it not make sense to render a line on topo because it just won’t be accurate aside from a “it’s kind of along this direction” at which point a precise line is not appropriate?