Depositing my two cents before these coins depreciate even further due to inflationary pressure:

name=* is defined as the primary name of the feature. For a feature in the natural environment, the primary name generally comes from either common or official usage (as opposed to a small placard someone found somewhere). The more well-known and widely known a natural feature, the more credence we typically give to common usage in case of conflict with official usage.

According to the multilingual name tagging scheme, name:*=* subkeys conform to the IETF’s BCP 47 standard, so name:en=* is defined as the primary name in the English language. We’re inconsistent about whether this is the name in the local dialect of English or according to a consensus of English dialects. For example, name:en=United States follows common American English, not the official name[1] or the customary name in British English.[2] On the other hand, name:en=Salt Lake City differs from the local dialect, which calls the city simply “Salt Lake”. But in these cases, neither name is particularly controversial, and user comprehension doesn’t suffer greatly from the use of one or the other.

BCP 47 also allows us to pair a language code with an ISO country code as shorthand for a “dialect”, so name:en-US=* would indicate the primary commonplace name in American English. Some languages like Chinese and Portuguese use country-qualified codes fairly frequently to accommodate different dialects. English doesn’t normally have so many naming differences that fall neatly along national dialectal lines. Usually our differences are about more practical matters, like what to call association football. In fact, American English is an umbrella term for the multitude of dialects of English spoken in the United States.

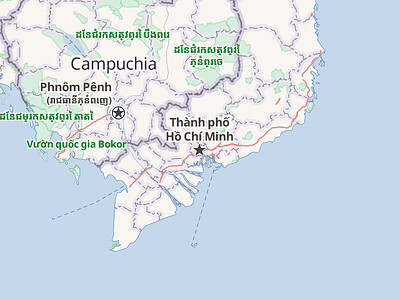

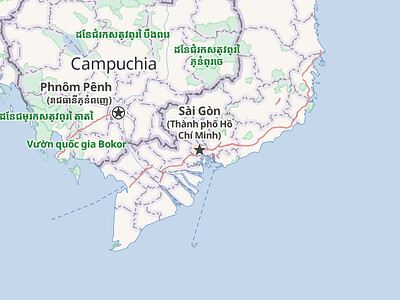

Unfortunately, this dialect tagging scheme clashes with the Data Working Group’s officially documented approach for indicating a geopolitical naming dispute. For example, the Vietnamese government takes the position that the South China Sea should be called the “East Vietnamese Sea” in English, contrary to what the Chinese and Philippine governments would prefer. Conversely, the U.S. federal government accepts the Vietnamese government’s name for Ho Chi Minh City, but ordinary Vietnamese speakers in the U.S. refuse to call the city by this name or let anyone else do so domestically. Few linguists recognize a “Vietnamese English” dialect or “American Vietnamese” dialect, but name:en-VN=* and name:vi-US=* can be understood as the names that would be commonplace in Vietnam when using English and in the U.S. when using Vietnamese, whatever the reason.

These country-qualified names discourage edit wars and politically motivated vandalism that contradicts the project’s consensus about the on-the-ground rule. So far, since I’ve added name:vi-US=* to Ho Chi Minh City, no one has unilaterally changed name:vi=* to Sài Gòn. This seems to work better than just adding alt_name=* or old_name=*, because name:vi-US=* appears right below the name that some people find objectionable in an alphabetically sorted list of tags. It might help that some data consumers can show the usual name to Vietnamese speakers except to those in the U.S., or that search engines that index one key will likely index the other with very similar behavior.

Still, “Gulf of America” has yet to enter common usage. Common usage matters in this case because the federal government created the name out of whole cloth and applied it to a feature it doesn’t fully control. Historically, we’ve been much more willing to promptly rename a country when the country decides to rename itself, or a mountain when the government renames it according to local wishes or longstanding unofficial usage. Without that basis, it would be prudent to exercise more caution. We haven’t seen, for instance, the National Geographic Society making any urgent moves. We haven’t even seen a sudden stop to the use of “Golf of Mexico”. (Which has been climbing again lately; such is the state of language and geography education in this country.)

Until then, official_name:en-US=* is probably the most recognition we can give this name for the time being.

Yes, this is a good precedent for us to follow. Maritime boundaries are multifaceted, so the more detail we can provide, the less potential for conflict and confusion. Most people don’t distinguish between the whole gulf and the territorial claims within it, so there may or may not be a long-term effect on how some people refer to the whole gulf, but at least a separately mapped maritime boundary could defuse the issue for a while.

The delimited boundaries between Cuba, Mexico, and the U.S. based on bilateral agreements are available from NOAA in the public domain, along with other valuable maritime boundary datasets. Hurry before anything happens to that climate science agency. Note that there’s a preexisting dispute between Mexico and the U.S. regarding both countries’ extended continental shelf.

Whatever happens to name=*, there’s a strong case for emphasizing the name Denali using reg_name=Denali. The Alaska Historical Commission has statutory authority over geographic names within the state (not binding on the federal government). So far, it seems unlikely that the AHC would’ve gone along with the federal renaming, so we might have a geopolitical dispute between a country and a political subdivision of that country. There is longstanding precedent for handling this situation in the U.S., including on federal property:

Various mappers over the years have attempted to expand it to “United States of America”, on account of the country’s abnormally large waistline in Mercator projection. ↩︎

As any BBC News presenter will tell you, it’s simply “America”. They care about making the map label fit even when the user puts the telly on its side. ↩︎